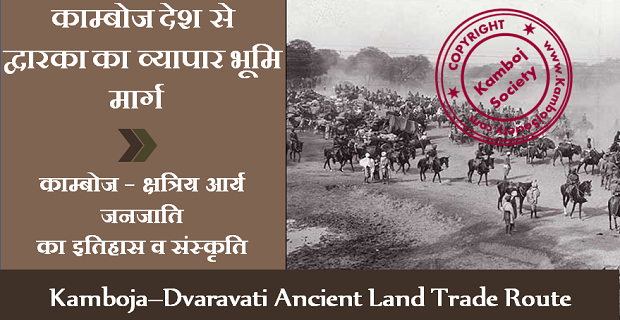

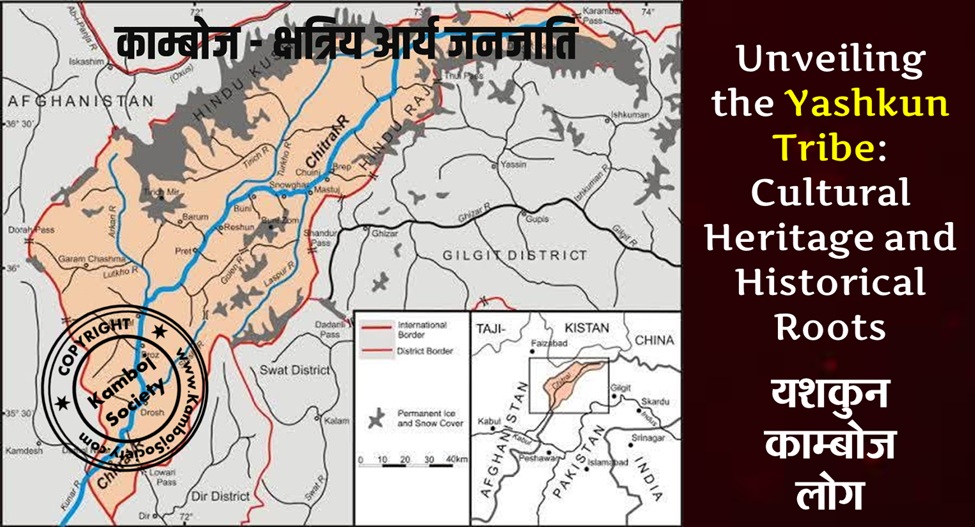

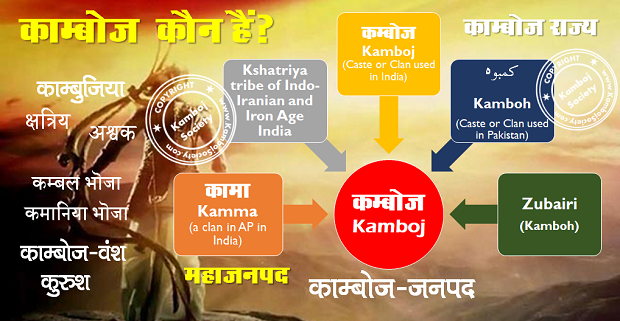

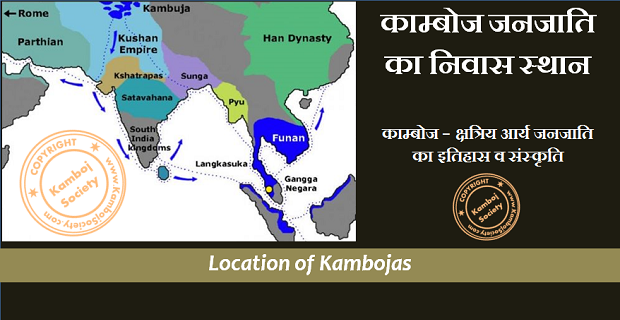

The Kamboja–Dvaravati Route is the name given in old Jataka literature to an ancient land trade route that was an important branch of the Silk Road during antiquity and the early medieval era. It connected the Kamboja Kingdom in today's Afghanistan and Tajikstan via Pakistan to Dv?rak? and other major ports in Gujarat, India, permitting goods from Afghanistan and China to be exported by sea to southern India, Sri Lanka, the Middle East and Ancient Greece and Rome. The road was the second most important ancient caravan route linking India with the nations of the northwest.[1]

The route

Land trade

Both the historical record and archaeological evidence show that the ancient kingdoms in the northwest (Gandh?ra and Kamboja) had economic and political relations with the western Indian kingdoms (Anarta and Saurashtra) since Pre-Christian times. This commercial intercourse appears to have led to the adoption of similar sociopolitical institutions by both the Kambojas and the Saurashtras.[1][6]Historical records

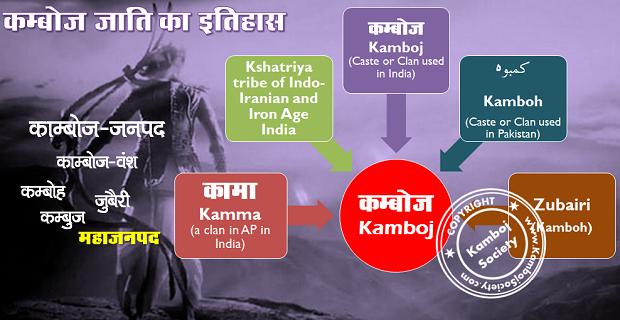

References in both Hindu and Buddhist scriptures mention trading activities of the ancient Kambojas with other nations:- The Arthashastra by Kautiliya, a treatise on statecraft written between the 4th century BCE and the 4th century CE, classifies the Kamboja and Saurashtra kingdoms as one entity, since the same form of politico-economic institutions existed in both republics. The text makes particular mention of warfare, cattle-based agriculture and trade.[8] The description tallies with those in the B?hat Sa?hit?, a 6th-century CE encyclopedia[9] and the major epic Mahabharata, which makes particular reference to the wealth of the Kambojas.[10]

- Buddhist sources such as literature in the Avad?na collection also refer to the "Kamboja-Dvaravati land road".[11]

Archaeological evidence

Numerous precious objects discovered in excavations in Afghanistan, at Bamyan, Taxila and Begram, bear evidence to a close trade relationship between the region and ancient Phoenicia and Rome to the west and Sri Lanka to the south. Because archaeological digs in Gujarat have also found ancient ports, the Kamboja–Dvaravati Route is viewed as the logical corridor for those trade items that reached the sea before traveling on east and west.[12]The seaport and international trade

From the port of Dvaravati at the terminus of the Kamboja–Dvaravati Route, traders connected with sea trading routes to exchange goods as far west as Rome and as far east as Kampuchea (Today's Cambodia). Goods shipped at Dvaravati also reached Greece, Egypt, the Arabian Peninsula, southern India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, the land of Suwannaphum (whose location has still not been determined) and the Indochinese peninsula. Dvaravati was, however, not the only port at the route's terminus. Perhaps more important was Barygaza or Bharukaccha (modern Bharuch, located on the mainland to the east of the Kathiawar peninsula on the river Narbada. Horse dealers from north-west Kamboja traded as far as Sri Lanka, and there may have been a trading community of them living in Anuradhapura, possibly along with some Greek traders.[13] This trade continued for centuries, long after the Kambhojans had converted to Islam in the 9th century CE.[14] The chief export products from Kamboja were horses, ponies, blankets embroidered with threads of gold, Kambu/Kambuka silver, zinc, mashapurni, asafoetida, somvalak or punga, walnuts, almonds, saffron, raisins and precious stones including lapis lazuli, green turquoise and emeralds.Historical records: western sea trade

The sea trade from the southern end of the Kamboja–Dvaravati Route to the west is documented in Greek, Buddhist and Jain records:- The 1st-century CE Greek work The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea{{Citation needed}} mentions several seaports on the west coast of India, from Barbarikon at the mouth of the Indus to Bharakuccha, Sopara, Kalyan and Muziris. The Periplus also refers to Saurashtra as a seaboard of Arabia.

- A century later, Ptolemy's The Geographia also refers to Bharakuccha port as a great commercial center situated on the Narbada estuary.[15] Ptolemy also refers to Saurashtra as Syrestrene.

- The 7th-century CE Chinese traveler Yuan Chwang calls Saurashtra Sa-la-ch'a and refers to it as "the highway to the sea where all the inhabitants were traders by profession".[16]

- Undated ancient Jain texts also refer to heavy trade activity in Saurashtran seaports, some of which had become the official residences of international traders.[17] Bharakuccha in particular is described as donamukha, meaning where goods were exchanged freely.[17] The Brhatkalpa describes the port of Sopara as a great commercial center and a residence of numerous traders.[18]

- Other ports mentioned in texts include Vallabhi (modern Vala), a flourishing seaport during the Maitraka dynasty in the 5th through 8th centuries CE. The existence of a port at Kamboi is attested in 10th-century CE records [19]

Archaeological evidence: western sea trade

There is good archaeological evidence of Roman trade goods in the first two centuries CE reaching Kamboja and Bactria through the Gujarati peninsula. Archaeologists have found frescoes, stucco decorations and statuary from ancient Phoenicia and Rome in Bamian, Begram and Taxila in Afghanistan.[21] Goods from Rome on the trade route included frankincense, coral of various colors (particularly red), figured linen from Egypt, wines, decorated silver vessels, gum, stone, opaque glass and Greek or European slave?women. Roman gold coins were also traded and were usually melted into bullion in Afghanistan, although very little gold came from Rome after 70 CE. In exchange, ships bound for Rome and the west loaded up in Barbaricum/Bharukaccha with lapis lazuli from Badakshan, green turquoise from the Hindu Kush and Chinese silk (mentioned as reaching Barbaricum via Bactria in The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea).[22]Historical records: eastern sea trade

The eastern and southern sea trade from the ports at the southern terminus of the Kamboja–Dvaravati Route is described in Buddhist, Jain and Sri Lankan documents.- Ancient Buddhist references attest that the nations from the northwest, including the Kamboja as well as the Gandhara, Kashmira, Sindhu and Sovira kingdoms were part of a trade loop with western Indian sea ports. Huge trade ships regularly plied between Bharukaccha, Sopara and other western Indian ports, and southern India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Suwannaphum and the Indochinese peninsula.[23][24] In particular, literature in the Buddhist Avad?na collection refers to a saint named Bahiya Daruciriya who was born in the port of Bharakuccha and who made several trade voyages. He sailed the length of the Indus seven times, and also travelled across the sea as far as Suwannaphum and returned safely home.[11] Also, the 4th century CE Pali text Sihalavatthu refers to Kambojas being in the Province of Rohana on the island of Tambapanni, or Sri Lanka.[25]

- An undated Jain text mentions a merchant sailing from Bharukaccha and arriving in Sri Lanka in the court of a king named Candragupta.[26]

- There is also a tradition in Sri Lanka, (recorded in the P?j?valiya) that Tapassu and Bhalluka, the two merchant brothers, natives of Pokkharavati (modern Pushkalavati) in what then was ancient Kamboja-Gandhara and now is the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan, "visited the east coast of Ceylon and built a Cetiya there.".[27] In addition, several ancient epigraphic inscriptions found in a cave in Anuradhapura refer to Kamboja corporations and a Grand Kamboja Sangha (community) in ancient Sinhala, as early as the 3rd century BC.[28]

- Several